Why Amazon Should Sell Electricity

Why don’t Costco, Chase Bank, or AT&T offer a residential electricity plan to their members? Wouldn’t it be natural to bundle the electric bill in with one of those relationships? Wouldn’t those companies love another $200/month per household of recurring, predictable, recession-proof, inflation-linked revenue? (Of course, I’m only talking about areas that allow retail competition for electricity).

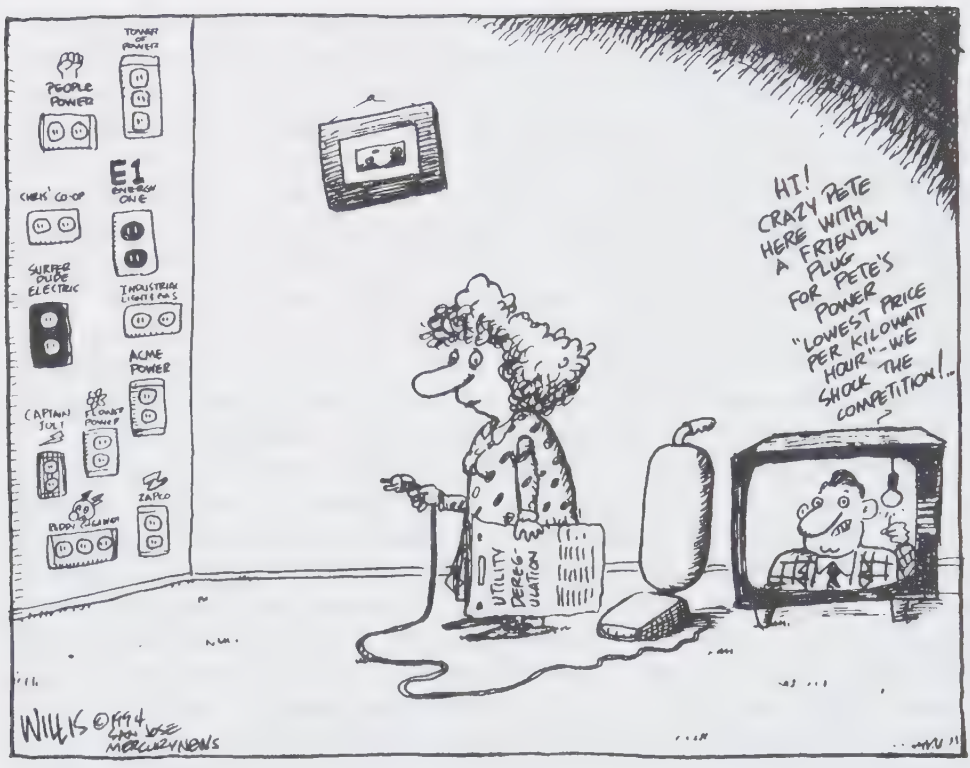

That was a part of the original vision of the deregulation of electricity retailing, but it hasn’t worked out that way. Nearly everyone still buys power from specialized power companies.

That’s because no company wants to either sink significant capital into buying power plants or otherwise take on significant liquidity risk. No business is more valuable when combined with electricity retail, so the $500 billion market remains in the hands of specialized power companies.

But Amazon is positioned to take this market.

For one thing, they’re already a massive player in the power sector whether they wanted to become one or not. Their data centers consume city-scale quantities of power. And to meet this load they’ve been the largest corporate buyer of bilateral power purchase agreements from 2020 to 2025. If they owned their capacity instead of contracted for it, they’d be the largest renewables owner in the US.

Amazon’s enormous data center load can cover them if they’re ever short on power. Being short means that their customer load is higher than the output of their power plants and any bilateral PPAs or financial power futures. Retailers live in fear of being short while wholesale power prices spike. But Amazon has a tool no one else does. If they’re short while prices are spiking, they can quickly turn off their data centers to reduce their total power imbalance.

Their advantages are strongest of all on the consumer-facing side. Of course they have an excellent brand and they own their own marketing channels. They also have the best smart home ecosystem, including a smart thermostat, which they could use to lower customer load to cover a short position. This works the same way as data centers, except with a lower opportunity cost.

But most powerful of all, they have an opportunity to de-commodify electricity by bundling electric service into the Prime ecosystem. This will take some explanation.

The electricity retail business

Electric retail is a huge industry but a challenging business.

On the surface it appears similar to any retail business. Because producers and consumers like to transact very differently (producers sell in bulk and pass on changes in cost while consumers buy in small quantities and want stable prices), the retailer bridges the gap.

The electricity retailer buys power from power producers at volatile wholesale prices, then sells it to consumers on fixed-rate plans. They keep the spread, the retail margin, between their average wholesale cost and their average retail price. So the name of the game is to grow your MWs of retail load and acquire the power to meet that load, as cheaply as possible.

But the electricity retailer does more than buy in bulk and sell in bits. They transform electricity from a commodity into a service. They buy electricity in spot transactions, but they sell it in the form of electric service plans that resemble revolving credit arrangements. The customer gets the right to consume power at a fixed fee, then pay at the end of the month.

That’s risky for the retailer. For one thing, there’s the risk that the customer doesn’t pay at the end of the month. But far more significant is the retailer’s liquidity risk.

Even if the retail rate is much higher than the retailer’s average wholesale cost, the retailer could still go bankrupt. Wholesale prices are extremely volatile. A large percent of system costs occur on a small number of days. The retailer will take significant one-day losses and have to build back their cash reserves over months from fixed-rate bill payments.

That’s why managing your power procurement is essential. This consists of forecasting how much power you’ll need - both forecasting the hourly load shape of their customer base and, more long-term, the size of their customer base - and then finding the lowest-cost ways to acquire the power to match that load.

There are four ways to procure power:

- buy it on the wholesale spot market,

- produce it yourself by owning your own power plant,

- buy exchange-traded power futures, or

- buy bilateral power purchase agreements.

The first two supply options have floating prices. You don’t know what future prices will be, but they tend to be volatile. If you’re going to be exposed to volatility, you’d rather be long than short. If your customers use more load than you can supply with options 2-4, then you’re ‘short’ and you’re forced to buy the balance on the wholesale spot market. This can lead to a liquidity crisis described above.

The cheapest way to acquire power is to produce it yourself - by owning a power plant that turns fuel into electricity. The power producer keeps the difference between their fuel cost and the price of power, called the spark spread, to compensate them for the risk they take in sinking significant capital into a power plant. If you own the plant, you keep that spread for yourself.

Between the two fixed-price supply options, PPAs and exchange-traded futures, PPAs have higher transaction costs but are probably better deals overall. That’s because as the PPA buyer you’re the “anchor customer” for a project under development. But that comes with the downside of longer-term (5+ year) agreements at a fixed price.

Long-term fixed prices are perfect if you’re an industrial power consumer (eg. a data center or factory). If you’re developing an industrial site, you’re underwriting to a 10+ year timeframe. You’re not trying to hyper-optimize your power costs over that period. If you’re offered a rate that works for you, you’d rather lock it in to take energy cost risks off the table. PPAs are a great tool for doing that.

But they’re more challenging for retailers. Retailers do need to hyper-optimize their power costs. Not only is it their primary cost, they’re competing with other retailers to provide the lowest retail rate possible. If they lock in their cost of service and then power prices fall (probably because natural gas prices fall), then their competitors that own their own generation can offer lower retail rates. Many of their customers will switch to the competitor, and they’ll be left holding out-of-the-money PPAs for more power than they now have customers for. This is also why the exchange-traded power futures curve isn’t liquid more than 2 years out.

Of course if you lock in a price and then prices rise, you’ll be able to offer lower rates than customers whose portfolios are more heavily weighted to owning their own generation. The major retailers seem to hedge, covering 40-60% of their retail load with their own power plants.

This ‘switching problem’ - the propensity of customers to switch retailers for small savings - is why Costco, Chase Bank, and AT&T, haven’t gotten into electricity retail. If they hedge their load with long-term fixed-price agreements and prices fall, then their customers will switch away from them. So they need to own some generation, but that’d tie up capital that could be better used for other purposes. So electricity retail remains in the hands of specialized power companies.

Every business that has long-term investments in its cost of service faces some version of the ‘switching problem’, but it’s so extreme in electricity retail because electricity is the perfect commodity. Electricity retailers can’t differentiate on quality, so they can’t differentiate on brand. They offer different plan structures or customer service quality, but the differences are marginal. All that’s left is price.

Some customers switch to the cheapest provider every year, while some never switch. The most competition is over the occasional-switchers. Retailers offer new customers very low, maybe even unprofitable, rates for a short term to get them to switch. Then they raise prices slowly over time.

So to summarize: Electric retail is a huge industry with large margins but significant risks. Those risks are liquidity risks from finding oneself short volatile spot prices and ‘switching risk’ from locking in prices that become uncompetitive. Amazon is positioned to neutralize both of those risks and become the leading power company in America.

De-commodifying electricity

Amazon is a big company with their hands in a lot of things, so they have many potential advantages in electricity retail. I touched on all of them at the start, and I’ll elaborate on them now that you have more context on the logic of the electricity retail business. But it all starts with Amazon’s opportunity to de-commodify electric service.

Direct Energy, a brand owned by a leading electricity retailer NRG Energy, offers free Amazon Prime (and/or an Echo Dot, though maybe not anymore) to new customers. It makes sense. Everyone loves Amazon, and Amazon’s brand is associated with the home. Customers don’t care about electricity rates, but they do care about free shipping on Amazon orders.

Well, if that’s a profitable promotion for Direct Energy, it would be a much more profitable promotion for Amazon. Because Amazon Prime is much cheaper for Amazon to offer than it is for Direct Energy.

And they can take this further. Amazon can offer lots of perks that are both compelling to consumers and nearly free for Amazon to provide. I don’t know the economics of Amazon Prime Video, Amazon Music Unlimited, or Audible, but it’s safe to assume that they are low marginal cost to provide. And there are lots of smaller benefits they can provide, like maybe sometimes the Amazon checkout says “Free Overnight, thanks to Prime Power”.

This changes the electricity customer’s calculus at renewal time from “ok, time to see who has the lowest rates these days” to “I’m going to stick with Prime Power because I get my Prime Video through that, and it’s Amazon so I’m sure their rates are competitive, I won’t even check”. The existing power retailers can’t compete with that.

By bundling electric service with differentiated services that customers value, Amazon can make their electric service plans sticky. Even if their rates become less competitive, they’ll experience much less switching.

This increased certainty about their future customer load has big implications. There’s less risk for them in serving more of their load with long-term PPAs. They’ll be able to meet their customers’ load using only renewable resources, and in a much more cash-efficient manner than buying power plants.

There’s still the possibility of finding themselves in a short position on power, which introduces liquidity risk. For example, maybe an unseasonably hot or cold day rolls in, spiking power demand above what Amazon had forecast when they bought their long-term hedges. This is where Amazon’s massive data center load comes into play.

Amazon can get out of any short position by turning off their massive data center load. It isn’t free, since there is a large opportunity cost to turning off a data center. But it’s an option that they have and their competitors don’t.

Their smart home ecosystem presents another opportunity for covering short positions. Amazon has the best smart home ecosystem, which includes a smart thermostat. They could use their control of customer thermostats to shape their load. For example, on a hot day where they expect to be short, they can smooth out their customers’ energy use by pre-cooling some homes to reduce demand during the expected highest priced hours.